Inde

With the on-going digital transformations in the economy, this repository of skills and knowledge could be harnessed and utilised effectively to bring about a productive transformation of the Indian economy. The development of digital infrastructure serves as an important approach for countries to elevate themselves in the digital value chains, which can be observed in a number of developing countries including India.

ILO’s Brief “Digital technologies and how India can use it to its advantage”, provides insight on building and developing digital infrastructure to address the digital divide; how digital technologies can be used for productive transformation of the society and economy; and how institutions can be strengthened in the digital era.

Skills systems are confronted by the need to respond to increasingly dynamic and fluid labour market and societal conditions. Climate change, technology, demographic shifts, migration and globalization are causing increasing disruption to the world of work, while making skills development increasingly complex, fluid and unpredictable. Addressing contemporary skills challenges requires more dynamic and integrated skills and lifelong learning ecosystems.

Recognizing the importance of innovation for the renewed calls for lifelong learning, the ILO has initiated the development of a Skills Innovation Facility. The Facility identifies and tests promising and innovative ideas and solutions that address the major skills challenges of today and of tomorrow.

Les systèmes de compétences sont confrontés à la nécessité de répondre à un marché du travail et à des conditions sociétales de plus en plus dynamiques et évolutifs. Le changement climatique, les technologies, les évolutions démographiques, les migrations et la mondialisation ont une incidence sur le monde du travail, tout en rendant le développement des compétences de plus en plus complexe, évolutifs et imprévisible. Pour relever les défis contemporains en matière de compétences, il est nécessaire de disposer des compétences plus dynamiques et intégrées et des écosystèmes d'apprentissage tout au long de la vie.

Reconnaissant l'importance de l'innovation pour favoriser l'apprentissage tout au long de la vie, l'OIT a lancé le Mécanisme d’innovation pour les compétences. Ce mécanisme permet d'identifier et de tester des idées et des solutions innovantes et prometteuses pour relever les principaux défis d'aujourd'hui et de demain en matière de compétences.

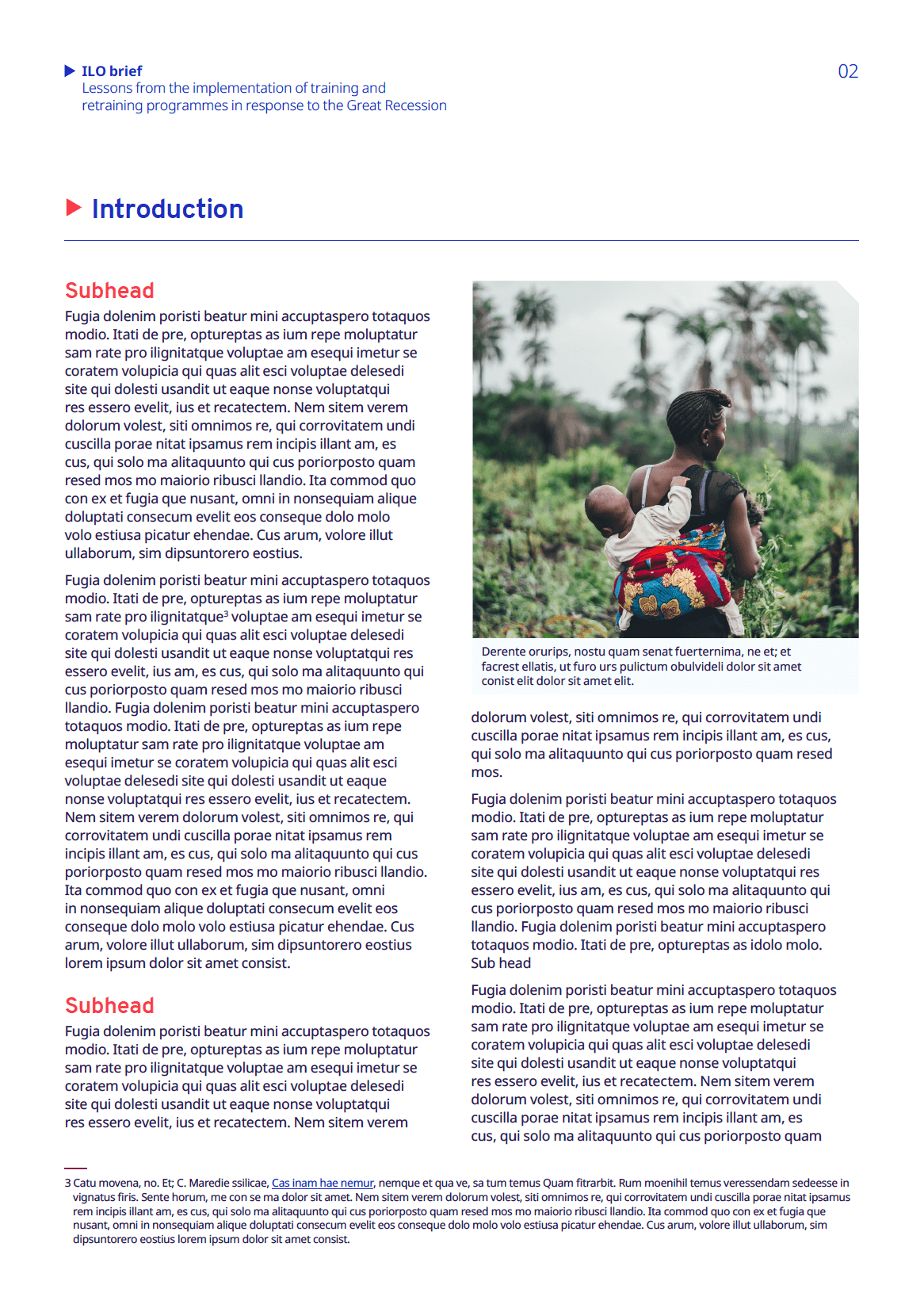

According to a 2018 ILO-UNICEF study entitled 'Skills, Education and Training for Girls Now', the global NEET rate, which measures the proportion of youth not in education, employment or training, is twice as high for female than male youth (at 31 and 16 per cent, respectively). In India, the NEET rate is 43 per cent for males and 96 per cent for females. What inhibits the transition of female youth from education to work? What leads younger women to drop out of the workforce, and what prevents them from returning to paid work later on? This blog discusses the barriers that female youth in India face in acquiring education and skills for improving their employability and proposes a set of measures that could help overcome such barriers.

To read the rest of this article, click on the PDF below.

When the Apprentices Act was first conceptualized in 1961, the infant Indian industry was largely manufacturing based under a license-quota regime along with an insignificant service sector. In the initial couple of decades of independence, our industry lacked adequate maturity and hence a prescriptive regime for notification of apprenticeship quota and strict controls may have been crucial.

The original Act was conceived almost six decades ago whereas sweeping changes have taken place in the Indian economy since then. Despite significant growth in the manufacturing sector, the emergence of an even larger service sector and the introduction of several vocational and other relevant courses beyond Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs), India was stagnating with 200,000 to 300,000 apprentices annually. This is a very small proportion of the 10 million people annually who aspire to join our labour force of 510 million workers. As against that, Germany and China have three and 20 million apprentices respectively. Clearly, the scale of apprenticeship in India has been abysmal.

Indian industry had been pleading for an apprenticeship regime that is business-friendly with reduced governmental controls. A process of countrywide consultation with industry was carried out to understand the challenges associated with apprenticeships. This eventually led to the emergence of a consensus that a self-regulated regime would lead to a sharp increase in the number of apprentices voluntarily trained by industry. Reforms propelled by Indian industry coupled with a long-drawn advocacy process and inter-ministerial consultations eventually resulted into amendments to the Apprentices Act passed by Parliament in 2014.

To read the rest of this article, click on the PDF below.

.png)